I was never one to believe in destiny. But, as a famous Armenian proverb says, you can’t escape it.

Earlier this month, I randomly googled my mother’s maiden name. In the list of search results, “Charles Mooshian” caught my eye.

I never met this man, my grandfather. He left our world more than 20 years before I entered it. But he is the sole reason I know live in Armenia. We were both passionate about communication, and when I write I think of him.

Charles is 25 percent of me. And that 25 percent qualified me to volunteer through the Birthright Armenia program in 2018. Through Birthright, I discovered the Emili Aregak Center for young people with disabilities in Gyumri, Armenia’s poorest city. After volunteering for a year, I now work as Development and Communications Officer. Our center’s mission is to promote the inclusion of youth with special needs in mainstream Armenian society through therapy, socialization, training and labor market integration. We also run Aregak Bakery, the first café in Armenia to intentionally employ young adults with disabilities.

So… back to destiny. When I clicked on my grandfather’s name in the search results, this blurb from a 65-year-old e-book popped up on the screen:

I was thunderstruck. My Armenian grandfather promoted inclusive employment practices in America, and now his American granddaughter is in Armenia doing the same! We are two communications specialists who never met, linked by blood and a cause, yet separated by time and space.

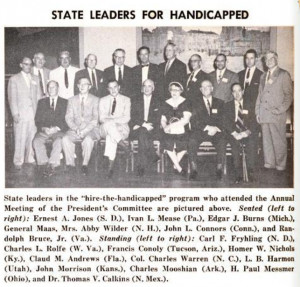

A closer look at the text revealed it to be the May 1954 edition of the publication The President’s Committee on the Employment of the Physically Handicapped. As I eagerly scrolled through the pages, I read of the nationwide effort—of which my grandfather had played a major role on the state level—to integrate people with disabilities into the American workforce. Beautiful passages like these caught my eye:

“…we must create the rehabilitation services and employment opportunities which are required to restore America’s handicapped to useful citizenship, integrate them into the activities of our economic and social life, and show them the dignity which is a birthright of all mankind.”

In my excitement, I could hardly focus on the moving words.

In conversations with my mother, I learned more about my grandfather’s fascinating life – that he was friends with William Fulbright and Douglas MacArthur, went on double dates with Ozzie and Harriet, and had monthly meetings with President Dwight Eisenhower during his stint on the President’s Committee on the Employment of the Physically Handicapped.

Amidst all these fascinating discoveries, I wanted to know what had spurred my grandfather’s passion for people with disabilities. With a growing family, a number of community and church positions and a full-time job, Charles had little time to spare for his demanding volunteer role on the President’s Committee.

According to my family, both Charles’ Christian faith and business savvy drove his work.

“Despite his difficulties as a husband and father, my father’s life was informed by the Bible and his love for Jesus,” my mom told me. “He knew that every person was made in the image of God and had something to contribute to society.”

My aunt agreed, but also added that Charles was adept in communication psychology. He knew that the language of “dignity” alone would not change hearts in the workplace. Thus, his “Hire the Handicapped” PR campaigns portrayed people with disabilities as an important resource that employers were overlooking.

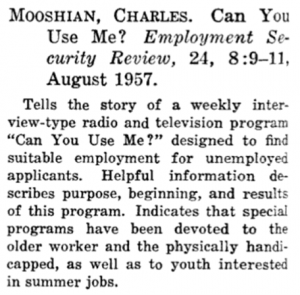

Charles’ interview-style radio and TV show called “Can You Use Me?” was an innovative means of broadcasting the skills of unemployed people through on-screen interviews. The concept of including people with disabilities in this pool of potential workers was very progressive for the 1950s when many employers were hesitant to consider them.

But those who took the risk ended up highly satisfied, according to my aunt’s memories.

“It turned out [people with disabilities] were better workers than most physically able people,” she told me. “They had the best attendance and there were certain jobs they could do that others couldn’t. They were so grateful to have the opportunity that nobody would give them.”

Images and stories used in my grandfather’s campaigns sought to prove this in striking ways.

My aunt recalls the story of the blind factory employee who was able to navigate through the challenges of a power outage. For him, darkness was the norm; for his colleagues, it was a source of panic.

Although she was quite young at the time, my mother was so impressed by one 1950s-era photograph that she could vividly describe it to me many decades later. It depicted a stylish young woman working a telephone switchboard with her feet. She didn’t have arms.

“Her toenails were polished, and she had a bracelet on her ankle and a ring on a toe,” my mom told me. “I imagined that if I were able to talk to her, she would say that there was nothing I could do with my hands that she couldn’t do with her feet!”

Always on the cutting edge of his field, my grandfather was passionate about wielding the power of sound and motion picture to communicate stories like these in an even more compelling manner than the written word. In his 1953 article Films on the Physically Handicapped, he explained the power of film to inspire change, citing examples and outlining detailed PR campaign ideas.

“Showing what the physically limited can do is far more important than the mere telling of it,” he wrote.

That line struck a deep chord in me, calling to mind one of the hashtags we have used in our campaigns at Aregak Bakery: #SeeThisAbility.

Hovo, one of the waiters at Aregak, has taught me the lesson that my grandfather knew so well. There is still deep stigma against people with special needs in Armenia; many people are blinded by wheelchairs or facial features when sizing up the capabilities of a person.

I don’t exclude myself from this; it’s a deeply ingrained human tendency that we must fight everyday. When I met Hovo, I knew that people with special needs have talents and abilities. What I didn’t realize is that they are uniquely skilled for certain work; in other words, Hovo is uniquely skilled to be a waiter. He’s a much better waiter than I could be! He and the other youth with whom I work have jarred a deep mental shift in my brain and heart.

At both Emili Aregak Center and Aregak Bakery, we care deeply about showing our community that children and youth with disabilities can thrive. And to do that, we focus on the therapies, activities and trainings that will cultivate their natural capabilities to the greatest extent possible. We must invest in them, like we do in all young people, to help them become their very best selves.

As a dual American-Armenian citizen, I am thrilled to be a bridge between my two countries, especially as it relates to helping youth with special needs. For example, in December, our speech therapist Margarita told me that she needed logopedic tools to help our kids with speech problems make even greater steps forward. When I discovered TalkTools, I was able to connect Margarita to equipment she would never have found in Armenia, including the TalkTools Spinner and Toothies. [see the attached video!]

Every day, I’m thankful for my work, for special needs kids, and for the companies and the people who come up with amazing solutions to help these kids thrive. Let’s continue to #seetheability in disability!